USMC How To: Be in Charge

Guided Discovery.

Are you taking ownership of your journey?

Suggested Reading

MCTP 6-10A, Sustaining the Transformation

Pages 4-1 through 4-24 based on printed document (PDF pages 49-72)

Description of general responsibilities and expectations of Marine Non-Commissioned Officers

Link to MCTP 6-10A on the US Marine Corps Publications Electronic Library

This week’s Study: Should I Stay or Should I Go Now

All excerpts below are from MCTP 6-10A

Guided Discovery

Recall the first time you were entrusted with some degree of professional responsibility.

For me, it was being asked to train new hires at McDonald’s. Even if it is relatively insignificant (those fries don’t make themselves!), the expectation evokes both pride and slight apprehension.

Now imagine the responsibility is not relatively insignificant.

“You are responsible for the accomplishment of your assigned mission and for the safety, professional development and well-being of the Marines in your charge.”

NCO Promotion Warrant

What the US Marine Corps expects from new non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and what is encouraged for individual development in an enlisted Marine’s first leadership position, given the weight of the responsibility, should be instructive for us all.

4-1. Earning a promotion into the NCO ranks is a significant accomplishment, one that necessitates returning to the reasons for serving and a fresh look at how to forge ahead.

While promotion is a significant accomplishment, its most important role is not that of a finish line, but as of a starting line.

4-1. Noncommissioned officers become both mentee and mentor, student and teacher, younger and elder sibling. This is a critical time when NCOs begin developing their own leadership style and accrue additional skills and tools to aid them in their duties.

Becoming an NCO is the start of a dual role, in which young Marine leaders are physically with junior ranks, responsible for junior ranks, and expected to continue to elevate their thinking, actions, decision-making, and career ambitions beyond that of junior Marines.

4-1. As an NCO, these requirements become less passive (receiving) and more active (seeking). An NCO must take the initiative to seek out leadership and instruction opportunities. This is a time when Marines should seek additional guidance from their mentors and leaders and devote additional time to self-reflection and learning.

The expectation is that NCOs take more ownership. Be more proactive. Seek. Own their development journey.

Are you taking ownership of your journey?

When challenged with greater responsibility, how do you organize your response?

The aptly titled Sustaining the Transformation suggests multiple areas of ownership for NCOs to seize to sustain both themselves and others at this stage of their development journey.

New Marine NCOs, to continue to progress in their development as leaders, must take ownership of:

Teaching

Translating

Making Choices

Strengthening Relationships

Maintaining Momentum

For a new NCO, the significant change in responsibility is not the size of the sphere of influence but rather the level of agency within the sphere. This is why ownership is so important. Failing to exercise agency is the abdication of responsibility and is counter-productive for both the new leader and the organization. Conversely, owning an individual journey is to the benefit of the individual on the journey, but also positively impacts those around the individual as well as the organization.

Own Teaching

While still a learner, a new leader is expected to become a teacher. Taking ownership of the teaching role is the most immediate way for a new leader to make an impact on those around them.

4-3. If a Marine struggles in one aspect, developing and devoting time to that shortcoming strengthens the whole Marine. In the end, owning one's successes and failures and learning from them strengthens and empowers young leaders to improve not only themselves, but their units as well.

The correct leader motivation, to improve oneself and those around them, is embodied in the act of teaching.

Teaching, in and of itself, also places greater responsibility on the teacher: owning the outcomes of the teaching. Owning teaching and engaging as an instructor is of value when the learners actually learn. Not all teaching and training will be equally successful; owning teaching also means owning the outcomes and understanding the obligation to keep working until teaching is successful.

This is accomplished through repetition and by appreciating that the opportunities to teach are all around us.

4-4. By treating every moment as an opportunity to learn, they continue to develop their own mental fitness, credibility, and knowledge, which they can pour into the Marines around them.

An added benefit is the reinforcement of the teacher-student dynamic, which humans naturally equate to a leader-follower relationship. Taking ownership of teaching builds credibility for new leaders while facilitating the development of an entire organization’s knowledge base.

What opportunities do you provide to high-potential employees to teach?

Do you enjoy teaching and seek opportunities, or wait for someone else to volunteer?

What mindsets need to change to make ‘every moment’ and opportunity to learn or teach?

Own Translation

4-6. Noncommissioned officers are translators of the commander's intent. They must speak two languages: the commander’s language, and the junior Marines’ language. Noncommissioned officers serve to take the task and purpose from the commander and present it to their Marines in such a way that every Marine knows their role and how to accomplish their assigned task.

Leaders at all levels, including new NCOs, have a requirement to convey orders and intentions from superior leaders and the organization. How messages are conveyed matters greatly. There is a significant difference between being a transmitter and a translator.

By definition, translation is putting information into the understood language. The text refers to this as speaking “the junior Marines’ language.” But it is more than that.

Everyone has worked for a leader that is too transparent when passing along plans or expectations with which they don’t agree: should shrugs and other forms of visual dismissiveness underscore a lack of alignment. This has never improved a single outcome for a team, nor does it ingratiate the leader with the team members.

Like any organization, the military has windows of opportunity for sharing feedback and windows of execution for taking orders. Owning translation is understanding the difference and acting appropriately.

4-6. By the time Marines are promoted to sergeant, they should be well-established as NCOs. It is expected that they grow past the loyalties to friendships in the junior ranks and begin looking at the larger Marine Corps picture. Increased responsibility, experience and training, as well as involvement in unit operations means the sergeant begins to see how the Marine Corps functions at a higher level.

It is also an ability to translate back up the chain of command. Junior team members, military or not, tend to express dissatisfaction and frustration in terms that more senior leaders categorize as whining. New leaders, living the duality of being with those they lead but needing to own translation are in a perfect position to frame upward feedback, both positive and negative, in a manner that is productive.

4-7. Noncommissioned officers should conduct themselves in a manner that drives and motivates others to reach the highest standard. This merging of leadership and personal accountability contributes to command climate and instills small-unit leadership values among those junior Marines who are watching.

How do you help direct reports connect daily work to your company's strategic objectives?

What do you do when you are not excited or pleased to translate organizational intent?

What techniques can you use to better ‘own’ translation?

Own Making Choices

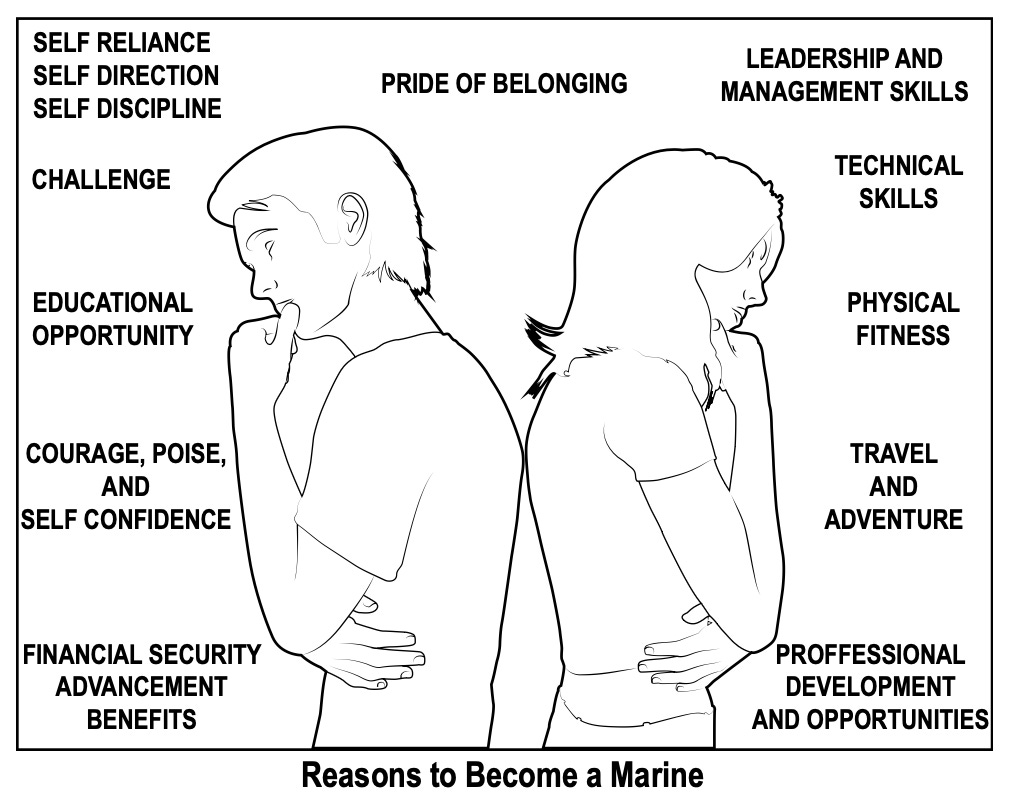

Discussed in this week’s Study, progressing to early levels of leadership presents young leaders with significant life choices. For members of the Armed Forces, owning the choice of staying in the military or leaving is typically the first in a series of many critical career decisions.

4.9 …a Marine will eventually have to answer two core questions: “Will other Marines benefit from me staying in?” and, “Will I benefit from staying in?”

Beyond reenlistment decisions, leaders will be constantly confronted with choices, both personal and professional, along their journey. Owning the choices means having agency in the decisions versus letting the needs of another or the organization continuously prevail.

The Marine Corps offers the below graphic to aid in evaluation of the choice for reenlistment, but it encapsulates the rationale to inform most choices any of us might have.

People pay for entire self-help books that are little more than making a personal scorecard out of the above graphic.

Make yourself a scorecard out of the above graphic for your current job (or role).

How satisfied are you in each area? What is lacking?

How would you prioritize this list for yourself, and are your priorities met or where shortfalls exists?

Own Strengthening Relationships (Mentors)

With a focus on self-sustainment, it is unsurprising that the Marine Corps would advocate seeking out and strengthening mentor relationships. A leader must own the process of finding the correct mentor so as to have agency in the outcomes of the mentorship.

4-13. Finding a mentor starts with two questions: “Where would I like to see myself?” and, “Who is a role-model I would like to emulate?”

…

For those looking for a mentor, it can be intimidating to seek out someone above one’s respective peer group. However, those are exactly the individuals whom we should reach out to. If they have achieved something we want to achieve, what better way to get there than to learn from someone who has done it?

Most senior leaders love the concept of mentoring and really love to talk. Owning the choice of a mentor is critical to make sure the mentor is talking about the subjects and perspectives that will make a difference to the junior leader.

4-14. Mentors can be found in unexpected places, and may not be like us at all, except that they’ve accomplished what we’d like to accomplish. A good mentor may be of a different faith, a different gender or race, in another branch of Service, or not in the military at all. Marines should evaluate their own biases to keep from missing out on valuable guidance and mentorship.

Owning the strengthening of mentor relationships should result in gaining multiple mentors with varied levels and perspectives to provide more robust coaching.

Learning to be a good mentee is also a development process. A process that a young leader can accelerate by investing the time to be a mentor for others.

4-14. In the process of finding one’s own mentor, remember that a good NCO may also mentor junior Marines.

Do you wait for mentorship to find you, or do you ‘own’ it by seeking it out?

How have your own preferences or biases limited your openness to potential mentors?

Owning Strengthening Relationships (Support Networks)

Beyond mentorship, new leaders must take ownership of strengthening relationships with broader support networks.

4-19. A support network is the scaffolding that keeps a Marine upright despite the winds that may blow around them.

Owning relationships with support networks means taking action to maintain, strengthen or initiate these networks versus leaving them up to chance or reliant on the efforts of other people.

4-20. With a support network, a Marine does not have to face any day alone. Many cultures and religious works have some version of the phrase, “Grief shared is grief divided. Joy shared is joy doubled.” Others phrase it as “Your joy is my joy; your sorrow is my sorrow.”

The risk of becoming self-absorbed and missing opportunities to share is typically a sin of omission versus commission. Time is the most difficult of assets to manage; failing to spend time on support relationships is the very definition of working harder and not smarter.

Feedback, encouragement, or tough love. All are needed from those we trust and love. But it needs to be sought out. Your support network is fully of equally busy people.

Though support networks may evolve, the non-negotiable factor influencing their value to a new leader is the individual leader’s investment in time with the network. If owning means taking action, action is evidenced by time.

It is also important to remember that just as you need support networks, you are part of the support network of others. These interactions are responsibilities.

4-19. The demands of life as a Marine can sometimes be understood only by fellow Marines. Having peers in one’s support network can help sustain the transformation when uniquely Marine Corps-related challenges arise.

What support networks do you rely upon? Are they sufficient?

What support networks are you in? Are you investing appropriately?

Owning Your Impact

4-24. The best way to influence Marines is to lead by example.

Owning your journey is acknowledging the impact of your actions and acting accordingly.

4-23. NCOs around the Corps set the example and establish expectations for those in their sphere of influence. Everything they do or do not do can influence the next generation of Marines.

There is no ability to side-step responsibility for a sub-set of actions as a new leader; everything is impactful to someone because someone is always watching and internalizing the lessons of a leader’s actions.

4-23. Many Marines who stay in the Corps can pinpoint positive and negative leaders they had throughout their enlistment. This shapes Marines’ outlook on the future when they ask themselves questions such as, “Do I want to be like my NCOs because they empowered me? or, “Do I want to be a better leader than my NCOs, because I feel they failed me?”

Are you taking ownership of your journey?

Are you proud of the example you set for others? What might you need to adjust?

Questions for Individual Reflection

Marines considering reenlistment ask "Have I left it better than I found it?" When evaluating your own professional trajectory, how would you answer this question about your current organization or activities?

What cultural or structural elements in your organization either promote or inhibit an ownership mindset among developing leaders?

Within your organization, who serves the translation function between strategic leadership and operational teams? How effective is this translation process, and what might improve it?

How do you purposefully manage the contagion of your attitude during organizational or personal challenges?

Professional Discussion Prompts

Reflect on how your organization identifies and addresses toxic leadership behaviors. What blindspots exist in your current approach?

Discuss how your organization balances character development with skill development in its leadership programs. Which side tends to receive more attention, and what are the consequences?

Marines are encouraged to have mentors for different aspects of life (professional, financial, spiritual). Discuss how your organization's approach to mentorship compares to this comprehensive model. What would a more holistic mentoring framework look like in your company?

How does your organization help mid-level leaders develop strategic perspective while maintaining operational excellence? Where are the gaps in this development process?

Personal Discussion Prompts

Reflect on your original motivations for entering your profession or joining your company. How have those motivations evolved over time, and what does this evolution tell you about your professional identity?

Describe the composition of your support network. Where might there be gaps, and how do these gaps affect your resilience during professional challenges?

Discuss a personal habit or practice that you've adopted specifically because of its potential impact on those who might be observing you as a leader.

Share how you've maintained or lost connection with people who knew you before your current professional identity was formed. How have these relationships influenced your leadership style?

Share experiences where your own advancement created relational complexity with former peers. How did you navigate these transitions?

Exercises

Purpose Translation Workshop

Exercise:

Each participant articulates their team's function in three progressively broader contexts: immediate operational goals, organizational strategy, and societal or industry impact.

In groups, members critique and strengthen each other's purpose translations, focusing on making abstract connections more concrete and meaningful.

Teams develop communication approaches for reinforcing these purpose connections with their own teams.

Debrief:

Which level of purpose translation proved most challenging to articulate clearly?

How might different team members respond to different levels of purpose framing?

What practices could embed purpose connections into daily operations?

Leadership Legacy Mapping

Exercise:

Each participant creates a "leadership legacy map" identifying key lessons they've learned from both positive and negative leadership examples throughout their career.

In groups, members identify patterns in these formative experiences and discuss how they've either perpetuated or counteracted these leadership approaches.

Teams develop specific practices for consciously shaping their own leadership legacy with current team members.

Debrief:

What negative leadership experiences have most shaped your own leadership approach?

How conscious or unconscious is your emulation of positive leadership models?

What feedback mechanisms would help you better understand your leadership legacy?

Feel free to borrow this with pride and use with your teams, professionally or personally. If you do, please let me know how it went and tips for improvement: matt @ borrowingwithpride.com