Problem Solving

Guided Discovery.

What problem are you trying to solve?

Suggested Reading

FM 5-0, Planning and Orders Production

Chapter 3, pages 45-54 based on printed document (PDF pages 59-66)

US Army perspective on structuring and logically addressing problems

This week’s Study: Your Problem Has a Type

All excerpts below are from FM 5-0 unless otherwise noted

Introduction

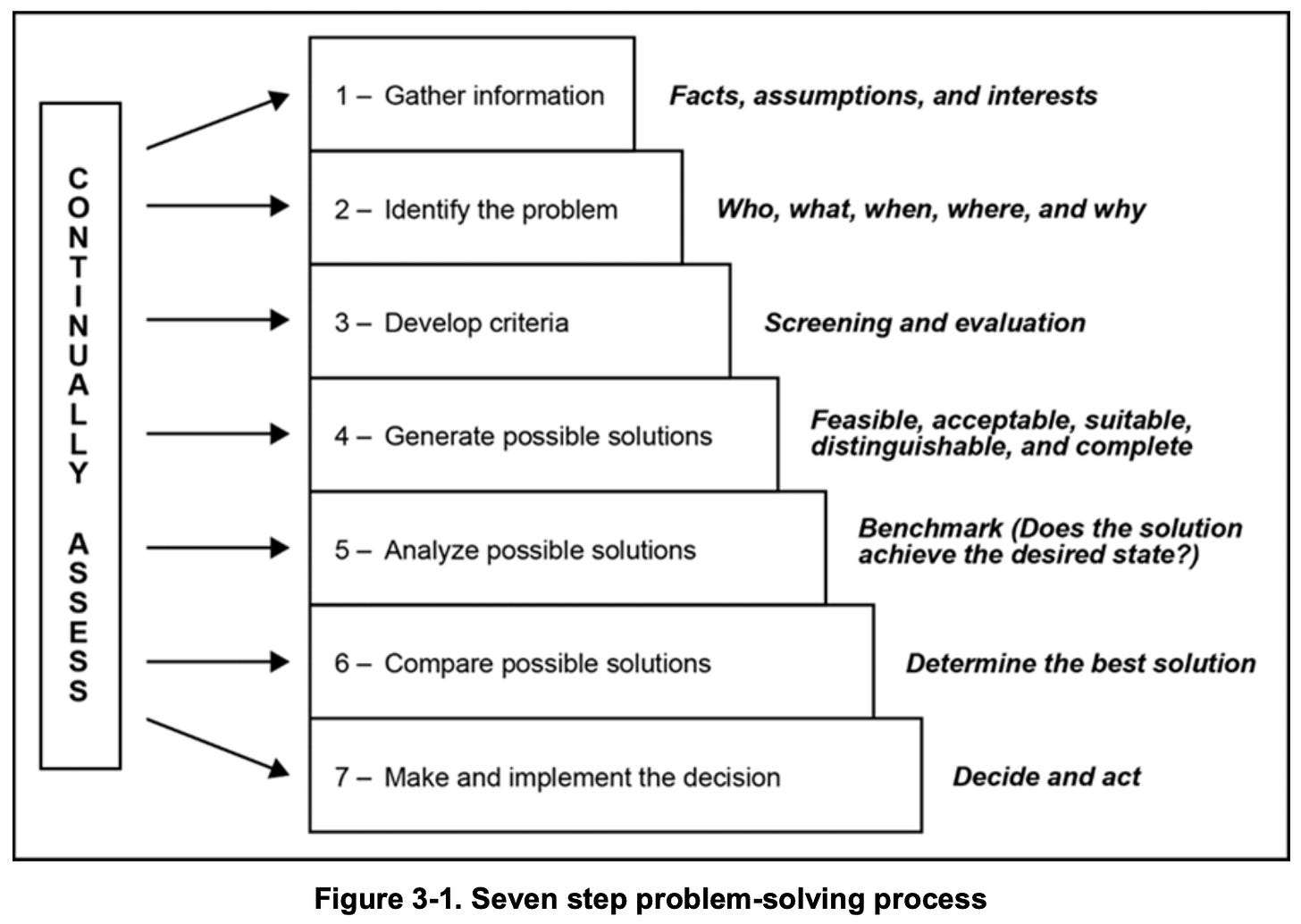

3-1. The ability to recognize and effectively solve problems is an essential skill for leaders. A problem is an issue or obstacle that makes it difficult to achieve a desired goal, objective, or end state. Army problem solving is a form of decision making. It is a systematic approach to defining a problem, developing possible solutions to solve the problem, arriving at the best solution, and implementing it. The object of problem solving is not just to solve near-term problems, but to also do so in a way that forms the basis for long-term success.

3-2. Not all problems require lengthy analysis to solve. For simple problems, leaders often make decisions quickly—sometimes on the spot. However, for complicated problems involving a variety of factors, a systematic problem-solving approach is essential. How much analysis is required to effectively solve a problem depends on the problem’s complexity, the leader’s experience, and amount of time available.

3-5. The art of problem solving involves subjective analysis of variables that, in many cases, cannot be easily measured. Leadership and morale, for example, are difficult to measure, but they may play a critical role in developing solutions to solve the problem. Problem solvers and decision makers make subjective assessments of such variables based on facts and assumptions and their likely effects on the outcome. Leader judgments are enhanced by their professional experience.

3-7. The structured nature of the Army problem-solving process … assists staff officers in identifying and considering key factors relevant to a problem. It also provides other officers with a framework for analyzing and solving problems. The Army problem-solving process helps to ensure that no key piece of information is overlooked in the analysis, thereby minimizing the risk of unforeseen developments or unintended consequences.

What problem are you trying to solve?

How do you develop life plans when family members define problems differently than you do?

Do your personal and professional plans solve problems or simply state desired end-states?

This Week’s Reading, Abridged

3-8. Problem solving is a daily activity for Army leaders, and it is often done intuitively. The Army problem-solving process is a systematic way to arrive at the best solution to a problem not easily solved intuitively. It applies at all echelons, and it involves the steps needed to develop well-reasoned, supportable actions. It incorporates risk discussion and risk management techniques appropriate to the situation. Army leaders remain as objective as possible when solving problems. The goal is to prepare an unbiased solution or recommendation for the decision maker, based on the facts. Problem solving is an important Army leadership action. It is essential to good staff work and command.

3-13. Both critical and creative thinking must intentionally include ethical reasoning-the deliberate evaluation that decisions and actions conform to accepted standards of conduct. Ethical reasoning within critical and creative thinking helps commanders and staffs anticipate ethical hazards and consider options to prevent or mitigate the hazards within their proposed solutions.

3-15. Well-structured problems are generally the easiest to solve. This is because with a well-structured problem—

All or almost all required information is available.

The problem is generally self-evident.

Known methods are available to solve the problem.

The problem displays little interactive complexity.

The problem is generally easy to recognize and place in categories.

There is typically a correct, verifiable answer.

3-16. Medium-structured problems are most of the problems Army leaders and problem solvers face. These types of problems fall between the extremes of well- and ill-structured problems. In partially structured problems, problem solvers may find that—

Leaders generally agree on its structure.

There may be more than one “right” answer.

Leaders may disagree on the best solution.

The problems require some creative skills to solve.

3-17. Ill-structured problems are the most challenging to understand and solve. With ill-structured problems—

Leaders often disagree on what the true problem is or cannot agree on a shared hypothesis.

Leaders often disagree on how to solve the problem.

The problems are complex and involve many variables, making them difficult to accurately analyze.

Leaders may disagree on the desired end state.

Leaders may disagree on whether an end state is achievable.

They may require multiple solutions applied concurrently or sequentially. Problem solvers must sometimes reduce complex ill-structured problems into smaller problems.

When and how does does misdiagnosing problem structure doom your solution?

What problems are you avoiding because they are ill-structured? What does this cost you?

How do you effectively problem solve when stakeholders have different definitions of success?

3-20. Leaders require facts and assumptions to solve problems. Understanding facts and assumptions is critical to understanding problem solving. In addition, leaders need to know how to handle opinions and organize information.

3-22. … Planners and commanders only use assumptions that are essential for the continuation of planning. In other words, an assumption is information that is accepted as true in the absence of facts, but at the time of planning cannot be verified. Appropriate assumptions used in decision making have two characteristics:

They are valid; that is, they are likely to be true.

They are necessary; that is, they are essential to continuing the problem-solving process.

3-24. When gathering information, leaders evaluate opinions carefully. An opinion is a personal judgment that the leader or another individual makes. Opinions cannot be totally discounted. They are often the result of years of experience. Leaders objectively evaluate opinions to determine whether to accept them as facts, include them as opinions, or reject them.

3-25. Organizing information includes coordination with units and agencies that may be affected by the problem or its solution. … As a minimum, leaders always coordinate with units or agencies that might be affected by a solution they propose before they present it to the decision maker.

3-28. When identifying a problem, leaders actively seek to identify its root cause, not merely the symptoms on the surface. Symptoms may be the reason that the problem became visible. They are often the first things noticed and frequently require attention. However, focusing on the symptoms of a problem may lead to false conclusions or inappropriate solutions. Using a systematic approach to identifying the real problem helps avoid the “solving symptoms” pitfall.

3-29. After identifying the root causes, leaders develop a problem statement-a statement that clearly describes the problem to be solved. When the leaders base the problem upon a directive from a higher authority, it is best to submit the problem statement to the decision maker for approval. This ensures the problem solver and decision maker agree on the problem to solve with updated guidance provided as necessary before continuing.

When does gathering more information become procrastination disguised as diligence?

What assumptions are you currently treating as facts and how might this blind you?

How do you prevent confusing your opinion, even backed by experience, with verifiable facts?

3-31. The third step in the problem-solving process is developing criteria. A criterion is a standard, rule, or test by which something can be judged—a measure of value. Problem solvers develop criteria to assist them in formulating and evaluating possible solutions to a problem. Criteria are based on facts or assumptions. Problem solvers develop two types of criteria: screening and evaluation.

3-32. Leaders use screening criteria to ensure that the solutions they consider can solve the problem. Screening criteria defines the limits of an acceptable solution. They are tools to establish the baseline products for analysis. Leaders may reject a solution based solely on the application of screening criteria. Leaders apply five categories of screening criteria to test a possible solution:

Feasible—fits within available resources.

Acceptable—worth the cost or risk.

Suitable—solves the problem and is legal and ethical.

Distinguishable—differs significantly from other solutions.

Complete—contains the critical aspects of solving the problem from start to finish.

3-33. … Well-defined evaluation criteria have five elements:

Short Title—the criterion name.

Definition—a clear description of the feature being evaluated.

Unit of Measure—a standard element used to quantify the criterion. Examples of units of measure are U.S. dollars, miles per gallon, and feet.

Benchmark—a value that defines the desired state or “good” for a solution in terms of a particular criterion.

Formula

When should you ignore your screening criteria to pursue breakthrough opportunities?

How do you applying creative thinking versus defaulting to old habits disguised as expertise?

How do you balance evaluation criteria between shareholder and other stakeholder demands?

3-37. Leaders generate options by developing various solutions to the identified problem. Each solution should generally address the following:

Does the solution achieve the desired end state?

What actions are required or what objectives must be achieved to reach the desired end state?

What resources are required for the solution?

What are the risks associated with the solution?

3-45. Leaders carefully avoid comparing solutions during analysis. Comparing solutions during analysis undermines the integrity of the process and tempts problem solvers to jump to conclusions. They examine each possible solution independently to identify its strengths and weaknesses. They are also careful not to introduce new criteria.

3-47. Quantitative techniques (such as decision matrices, select weights, and sensitivity analyses) may be used to support comparisons. However, these are the tools to support the analysis and comparison. They are not the analysis and comparison themselves. The quantitative techniques should be summarized clearly so the reader need not refer to an attachment for the results.

3-49. A good solution can be lost if the leader cannot persuade the audience and decision maker that it is correct. Every problem requires both a solution and the ability to communicate the solution clearly and effectively. The writing and briefing skills a leader possesses may ultimately be as important as good problem-solving skills.

When is a ‘good enough’ solution more dangerous than no solution at all?

Does your life planning consider multiple solutions? Do you give yourself options?

What problem are you trying to solve?

Questions for Individual Reflection

When does your instinct to move fast prevent you from solving the correct problem?

What is the difference between a problem that ‘makes it difficult to achieve a desired goal’ versus symptoms, and what techniques do you use to recognize the delta?

When does your desire to remain objective in problem-solving introduce bias through what your choice in measurements?

How can you tell if you are solving the problem or just implementing a predetermined solution to which you are already attached?

How do you balance systematic thinking with emotional intelligence in life planning?

Professional Discussion Prompts

How do you distinguish between solving symptoms versus root causes when quarterly pressure demands immediate results?

When and why is it ever worth solving the wrong problem well versus solving the right problem poorly?

How do you structure problem-solving when the solution requires capabilities you or your team do not possess?

How do you evaluated whether a problem ‘ill-structured’ because of genuine complexity versus organizational politics?

How do you coordinate with ‘units that might be affected’ when those units are competitors, regulators, or activist investors?

Personal Discussion Prompts

What personal assumptions do you treat as facts in your closest relationships?

What problems in your personal life are you avoiding because they are too complex? What needs to change?

What evaluation criteria do you unconsciously use when making major life decisions? What needs to change?

How do you brainstorm family decisions when ‘unrestrained participation’ conflicts with a need to maintain parental authority?

What feedback systems do you have for monitoring whether your personal solutions created new problems? How often do you review?

Exercises

Problem Statement Reality Check

Exercise:

Each member brings a current business problem faced by them or their team.

Apply the Army's root cause questions: compare current to desired state, define scope, answer who/what/when/where/why.

Rewrite problem statements after systematic analysis.

Debrief:

How many of your problems were actually symptoms of deeper issues?

What changed when you defined scope and boundaries systematically?

Which root causes require solutions outside your direct control?

Screening Criteria Development

Exercise:

Design screening criteria (feasible, acceptable, suitable, distinguishable, complete) for a transformation initiative.

Apply criteria to both incremental and breakthrough solution options.

Identify how screening criteria might eliminate more revolutionary possibilities.

Debrief:

When do your screening criteria embed status quo thinking?

How might risk criteria filter out necessary disruption?

How challenging is it to agree on criteria and why?

Feel free to borrow this with pride and use with your teams, professionally or personally. If you do, please let me know how it went and tips for improvement: matt @ borrowingwithpride.com