Prioritizing Development

Guided Discovery.

How do you develop people?

Suggested Reading

ADP 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession

Pages 6-1 through 7-4 based on printed document (PDF pages 79-98)

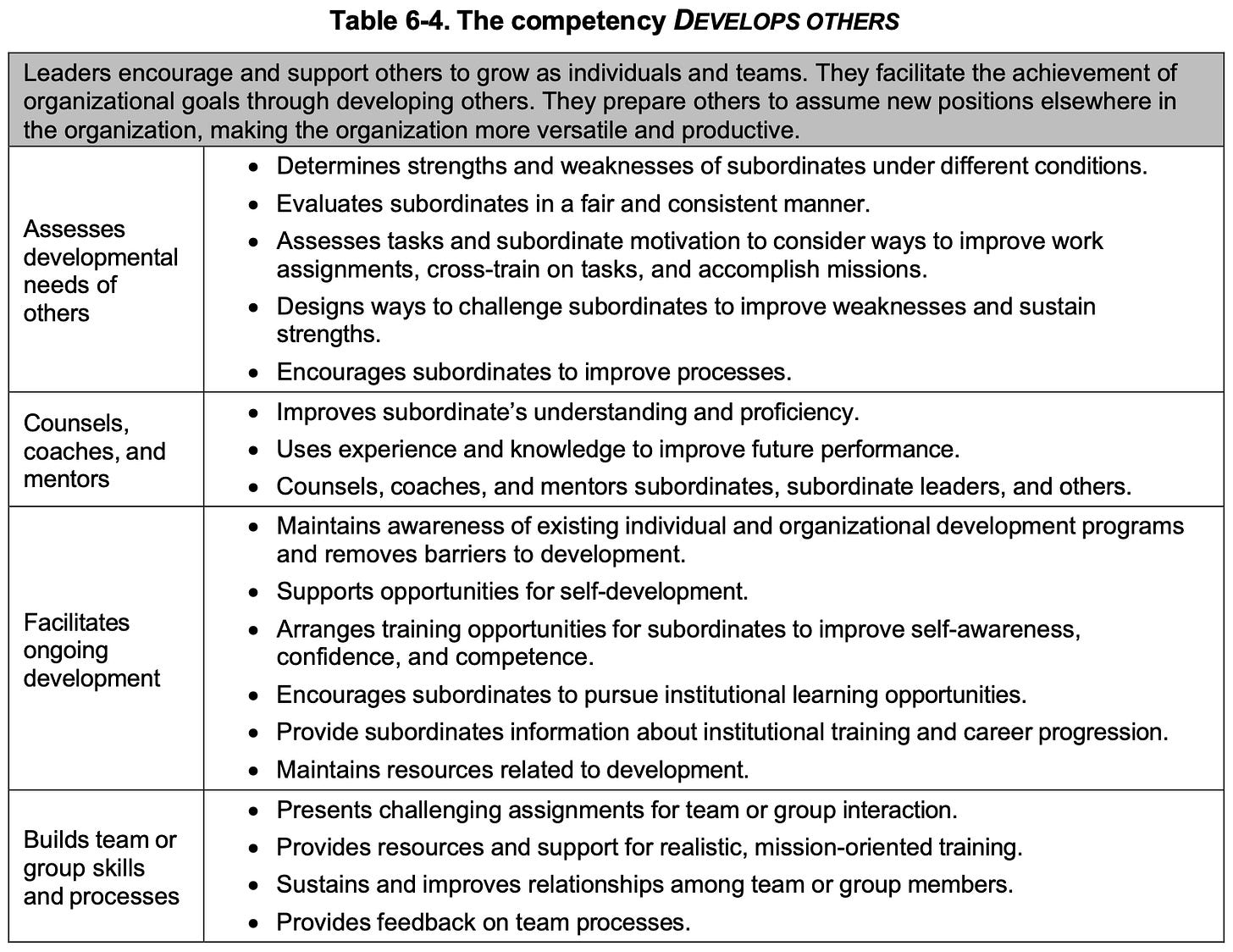

Reviewing the US Army’s five competencies for developing and achieving: prepares self, creates a positive environment, develops others, stewards the profession, and gets results

This week’s Study: Train Your Replacement

All excerpts below are from ADP 6-22 unless otherwise noted

Introduction

6-2. Leaders develop their own leadership proficiency through deliberate study, feedback, and practice. Fundamentally, leadership develops when an individual desires to improve and invests effort, their superior supports development, and the organizational climate values learning. Learning to be a leader requires knowledge of leadership, experience using this knowledge, and feedback from one’s seniors, peers, and subordinates. It also requires opportunities to practice leading others as often as possible. Formal systems such as evaluation reports, academic evaluation reports, and 360 assessments offer learning opportunities, but the individual must embrace the opportunity and internalize the information. The fastest learning occurs when multiple challenging and interesting opportunities to practice leadership with meaningful and honest feedback are present. These elements contribute to self-development, developing others, and setting a climate conducive to learning.

6-3. Leader development of others involves recruiting, accessing, developing, assigning, promoting, and retaining the leaders with the potential for levels of greater responsibility. Leaders develop subordinates when they prepare and then challenge them with greater responsibility, authority, and accountability. It is the individual professional responsibility of all leaders to develop their subordinates as leaders.

6-5. Committed leaders continuously improve their organization, leaving it better than they found it. They expect other leaders to do the same. Leaders look ahead and prepare subordinates with potential to assume positions with greater leadership responsibility; in turn, subordinates develop themselves to prepare for future leadership assignments. Leaders ensure subordinates know that those who are best prepared for increased responsibility are those they are most likely to select for higher leadership positions.

How do you develop people?

How do you prioritize developing skills that do not yet exist in your industry?

Do your development priorities reflect your deepest values or your greatest fears?

This Week’s Reading, Abridged

6-9. Successful self-development concentrates on the key attributes of the leader: character, presence, and intellect. … Leaders must exploit every available opportunity to sharpen their intellectual capacity and relevant knowledge. A developed intellect enables the leader to think creatively and reason analytically, critically, ethically, and with cultural sensitivity.

6-12. Leaders read about, write about, and practice their profession. They prepare themselves for leadership positions through lifelong learning and broadening experiences relevant to their career paths. Lifelong learning involves study to acquire new knowledge, reflection, and understanding about how to apply it when needed. Broadening consists of those education and training opportunities, assignments, and experiences that provide exposure outside the leader’s narrow branch or functional area competencies. Broadening should be complementary to a leader’s experience, and should provide wider perspectives that prepare the leader for greater levels of responsibility.

6-15. Leaders develop self-awareness though self-critique and self-regulation. Self-aware leaders are open to feedback from others and actively seek it. They possess the humility to ask themselves hard questions about their performance, decisions, and judgment. They are serious about examining their own behavior to determine how to be a better, more effective leader. Self-aware leaders are reflective, hold themselves to higher standards than their subordinates, and look to themselves first when subordinates are unsuccessful.

6-16. Self-aware leaders understand they are a component of a larger organization that demands both adaptability and humility. They understand the importance of flexibility because conditions continuously change. They also understand that the focus is on the mission, not them.

6-17. Competent and confident leaders make sense of their experience and use it to learn more about themselves. ... Self-critique can be as simple as posing questions about one’s own behavior, knowledge, or feelings or as formal as using a structured set of questions about an event.

Critical questions include—

What happened?

How did I react?

How did others react and why?

What did I learn about myself based on what I did and how I felt?

How will I apply what I learned?

What happens when your development priorities conflict with what people actually want?

How do you prioritize self-development when people depend on your current expertise?

Can, or when does, continuous learning become an excuse for indecision?

6-22. Culture is a longer lasting and more complex set of shared expectations than climate. Culture consists of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterize the larger institution over time. The Army’s culture is deeply rooted in tradition. Leaders refer to Army’s culture to impress on Army personnel that they are part of something bigger than themselves. Soldiers and DA Civilians uphold the Army’s culture to honor those who have gone before and those who will come after.

6-23. Climate is a shorter-term experience than culture and reflects how people think and feel about their organization. Climate depends upon a network of personalities within a unit that changes as Army personnel come and go. A unit’s climate, based on shared perceptions and attitudes, affects mutual trust, cohesion, and commitment to the mission. A positive climate ensures Soldiers and DA Civilians are engaged and energized by their duties, work together as teams, and show respect for each other.

6-25. Leaders make it a point to dialogue with subordinates about the conditions of their lives and the unit to get a sense of the climate. Communicating goals openly provides subordinates a clear vision to achieve. Communication between subordinates and leaders is essential to achieve and maintain a positive climate. Leaders inspire and motivate subordinates to bring creative and innovative ideas forward and they seek feedback from subordinates about the climate. Openly taking part in unit events and activities increases the likelihood that subordinates perceive leaders are concerned about the group’s welfare and has the group’s best interests at heart.

6-28. Leaders need to continually assess the organizational climate, realize the importance of development, and work to limit any zero-defect mentality. Recognizing the importance of long-term sustainability and sharing and encouraging feedback (both positive and negative) should be a priority for all team members. Leaders create positive climates by treating all fairly, maintaining open and candid communications between other leaders and subordinates, and creating and supporting learning environments.

6-34. Leaders should be able to resolve two kinds of conflicts: work-related and personal. Any given conflict is likely to contain some level of both elements. Work-related conflict can stem from disagreement over a course of action, workload perceptions, or the best steps for completing a specific task. Personal conflicts generally stem from people who do not like or respect each other or some perceived grievance based upon individual behavior. Leaders need to develop the skills to address both types of conflicts as rapidly and effectively as possible. Conflicts that simmer lower the morale and duty performance of those involved and can corrode an organizational cohesion when not quickly addressed.

6-38. Historians describing great armies often focus on weapons, equipment, and training. They may mention advantages in numbers or other factors easily analyzed, measured, and compared. However, many historians place great emphasis on two factors not easily measured: esprit de corps and morale.

6-40. Leaders who foster tradition and an awareness of history build camaraderie and unit cohesion, becoming esprit de corps.

Can building team cohesion stifle innovation? How do you avoid groupthink?

How do you maintain competitive advantage while encouraging open knowledge sharing?

What personal traditions do you maintain to build esprit de corps in your family?

6-46. A leader has the responsibility to foster subordinates’ learning. Leaders explain the importance of a particular topic or subject by providing context—how it will improve individual and organizational performance.

6-47. Learning from experience is not always possible—leaders cannot have every experience in training. Taking advantage of what others have learned provides benefits without having the personal experience. Leaders should share their experiences with subordinates through counseling, coaching, and mentoring sessions; for example, combat veterans can share experiences with Soldiers who have not been in combat. Leaders should also take the opportunity to write about their experiences, sharing their insights with others in professional journals or books.

6-52. Leaders have three principal roles in developing others. They provide knowledge and feedback through counseling, coaching, and mentoring.

6-59. Working in real settings—solving real problems with actual team members—provides challenges and conditions where leaders see the significance of leadership and practice their craft. Good leaders encourage subordinates to develop in every aspect of daily activities and should seek to learn every day themselves. The operational domain includes the three factors of leader, led, and situation and provides real tasks with feedback.

6-60. Good leaders seek ways to define duties to prepare subordinates for responsibilities in their current position or next assignment. ... Leaders can rotate into special duty assignments to give them broad leadership experiences and be given stretch assignments or tasks to accelerate their development.

6-63. Leaders must guide teams through three developmental stages: formation, enrichment, and sustainment. Leaders remain sensitive to the fact that teams develop differently and the boundaries between stages are not absolute. The results can determine what to expect of the team and what improves its capabilities. Understanding the perspectives of team members is important. Leaders understand that the national cause, mission, purpose, and many other concerns may not be relevant to the Soldier’s perspective. Regardless of larger issues, Soldiers perform for others on the team, for the Soldier on their right or left. A fundamental truth is that Soldiers accomplish tasks because they do not want to let each other down.

How do you balance developing depth versus breadth in your organization?

When does prioritizing team development undermine individual accountability?

6-75. Developing multiskilled leaders is the goal of preparing self and subordinates to lead. An adaptable leader will more readily comprehend the challenges of constantly evolving conditions, demanding not only warfighting skills, but also creativity Army leaders who reflect upon their experiences and learn from them will often find better ways of doing things. Leaders must employ openness and imagination to create effective organizational learning conditions. Effective leaders are not afraid to underwrite mistakes. They allow others to learn from them. This attitude allows growth into new responsibilities and adaptation to inevitable changes.

7-2. A leader’s primary purpose is to accomplish the mission. Leadership builds and guides the effective organizations necessary to do so. Leaders require a focus on the future that views building and maintaining effective organizations as critical to mission accomplishment. Building effective Army organizations serves the larger purpose of mission accomplishment. Mission accomplishment takes priority over everything else, especially in combat where their unit may be at risk of destruction.

7-4. Many matters consume a leader’s time and attention. Leaders have obligations that are far ranging and at times are contradictory. Leaders make these challenges transparent to their subordinates whenever possible. Leaders are responsible to create conditions that enable subordinates to focus and accomplish critical tasks.

7-9. When teams stress over high workloads, leaders should intervene to prioritize tasks and mitigate the causes or symptoms of seemingly insurmountable workloads. As a preventive step, planning aids even distribution of tasks—mission prioritization allows followers to know where to place effort or what to delay or suspend. Other measures require leaders to shield or protect subordinates from excessive taskings when possible and to ensure appropriate resources are available. A long-term measure is to develop individuals and train teams through cross training to be capable of assuming high workload levels. Effective communications allows members to prepare themselves to handle greater levels of workload or handle the effects of stress that the workload places on them. Morale-building activities, wellness and resilience steps, and grantingbreaks from operational rigors when possible, can also help address stress. Successful organizations have leaders who understand workload levels and are proactive in mitigating stress or stressors.

What's your organization's actual tolerance for the "learning from mistakes" philosophy?

How do you create psychological safety for team members while maintaining performance accountability?

7-10. Many leaders struggle with delegation, from the newly promoted to the most experienced who simply take on too much. Moving from an individual contributor to overseeing the efforts of others can be challenging. It requires leaders to spend their time differently and develop different skill sets this includes balancing workloads and avoiding overtasking subordinates. Some leaders may experience the opposite situation by delegating too much. Some basic guidelines apply to all leaders:

Delegating improperly, or failing to delegate at all, leads to organizational failure.

A leader’s role is to ensure the task is accomplished, not to complete the task personally.

While completing daily, weekly, and monthly planning and reflection, leaders ask, “What am I doing that I should delegate?" “What do I delegate that I should not?”

Leaders cannot develop subordinates without delegating to them.

Leaders cannot adjust and expand their unit’s capabilities without delegating.

7-12. To accomplish missions consistently, leaders need to maintain motivation within the team. One of the best ways to do this is to recognize and reward good performance. Leaders who recognize individual and team accomplishments promote positive motivation and actions for the future. Recognizing individuals and teams in front of superiors and others gives those contributors an increased sense of worth. Leaders seek opportunities to recognize the performance of their subordinates. They do this by crediting their subordinates for the work they do. Sharing credit has enormous payoffs in terms of building trust and teams.

When does empowering others become abdication of leadership responsibility?

How do you model self-development while managing career demands?

How do you develop people?

Questions for Individual Reflection

What is the difference between mentoring and developing successors who might replace you? Does it matter?

How do you measure the ROI of investing in people who will likely leave for competitors?

What is the business case for developing talent that benefits your successor or another team more than you?

How do you balance developing high performers versus rescuing struggling team members?

When should market volatility override long-term development commitments? How do you evaluate the tradeoff?

Professional Discussion Prompts

Which costs more: over-developing talent that leaves or under-developing talent that stays?

What is the business case for developing people beyond their current role requirements?

How do quarterly pressures distort your development investment decisions?

How do you allocate development resources when everyone claims to be high-potential?

What is the optimal ratio between internal development versus external hiring?

Personal Discussion Prompts

How do you handle feedback from people who matter to you personally?

How do you create a positive environment at home after a difficult day at work?

How are your children's development needs similar or different from workplace development challenges?

How do you balance developing yourself versus being present for family development?

What aspects of yourself do you avoid developing? Why?

Exercises

Development Audit

Exercise:

Participants individually map their last three direct reports' career trajectories post-departure from the team.

Share findings. Identify patterns in who succeeded, who failed, and why.

Discuss what this reveals about their actual (versus intended) development impact.

Debrief:

What does your development batting average tell you about your methods?

Which of your former people would you hire back and what does that reveal?

Delegation Assessment

Exercise:

Individuals identify tasks they should but do not delegate and explore the real reasons why they do or do not delegate.

Share what they're protecting (expertise, relationships, control) by not delegating.

Discuss the cost to their subordinates’ development of their delegation choices.

Debrief:

What are you afraid will happen if you truly let go?

How much of your indispensability is manufactured by your delegation choices?

Feel free to borrow this with pride and use with your teams, professionally or personally. If you do, please let me know how it went and tips for improvement: matt @ borrowingwithpride.com