Developing Leaders

Guided Discovery.

How much do you work on your own development?

Suggested Reading

FM 6-22, Developing Leaders

Pages 1-1 through 1-7 based on printed document (PDF pages 15-21)

An overview of the US Army’s leader development tenets, definitions, and expected evolution over a career

This week’s Study: Be - Know - Do

All excerpts below are from FM 6-22

Guided Discovery

Leader development by walking around—the continual face-to-face engagement by leaders during daily duties—is the most effective informal means of developing leaders at the platoon, company, battalion, and brigade level.

FM 6-22

You should view leader development and your own personal development as one.

1-1. There is no more important task for the U.S. Army than developing its people to lead others to defeat any enemy, anywhere. Developing leaders is inherently part of every garrison activity, training event, and real-world operation Army forces conduct around the world. Each leader–subordinate interaction is a development opportunity. They are inseparable from training, enforcing standards, providing feedback, and setting a personal example.

Whether in actual leadership roles or not, we are all working to influence the world around us. The most straightforward and intentional way of doing so is by leading. What leading means is not generic, define it how you like. But it is core to our development journeys.

1-3. Leaders develop through career-long synthesis of the training, education, and experiences acquired through opportunities in the institutional, operational, and self-development domains.

The three domains for development: institutional, operational, and self, are reinforcing. But the driving pillar of the three must be self. Relying wholly on an institution, usually your employer, to drive your development will result in a flatter trajectory and longer timeline, even if you have a wonderful employer and strong internal champions. Self-development is critical, both to structure objectives and goals for institutional and operational development, as well as to serve as the point of synthesis and evaluation for those areas of development.

What are you expectations from each domain in your development journey?

How reliant are you on the institutional domain to define your journey?

And what of those other domains? Is there a hierarchy? I’d interpret the Army as suggesting there is.

1-4. Significant leader development occurs during professional education, unit leader development programs, and counseling sessions. However, Army research shows the most effective developmental experiences occur in the operational domain, during daily interactions with subordinates as they prepare for and execute missions.

How I would propose thinking of the three domains of development:

If you ensure you are focusing on self-development and operational development (by applying a learning & development lens to all daily interactions, the institution domain becomes a capstone. It is often times the best opportunities to receive formal feedback on your individual development.

1-5. Developing leaders and being developed by others requires mutual understanding between leaders and subordinates—both about the work involved in developing others and work needed to become a good leader. The developmental experience can be challenging and requires openness and a willingness to take risks and learn from experiences (both successes and failures). Those who lead and develop other leaders must treat experiences as lessons learned sources.

Where are you able to take risks in your development journey?

Do you have sufficient formal sources of feedback? How might you prompt them?

Do you have sufficient informal sources of feedback? Where might you find them?

In addition to the concept of the mutually supportive domains to enable education, training, and experiences, the US Army suggests four additional tenets to leader development.

1-6. Tenets of developing leaders are the essential principles that make the Army successful at developing its leaders. The tenets provide a backdrop for the Army’s unit training principles (see ADP 7 0). The overarching tenets are—

Strong commitment by the Army, superiors, and individuals to developing leaders.

Clear purpose and intention for what, when, and how to develop leadership.

Supportive relationships and culture of learning.

Three mutually supportive domains (institutional, operational, and self-development) that enable education, training, and experiences.

Providing, accepting, and acting on candid assessment and feedback for self-awareness.

Spend a moment contemplating the first tenet: Strong commitment by the Army, superiors, and individuals to developing leaders. Beyond the practical imperative to develop leaders, consider that the act of training others to lead is itself a leader development tool. Leaders must be trainers. Helping to develop others is another method of self-development.

1-10. Development depends on having clear purpose for why, what, when and how to develop. Good leader development is purposeful and goal oriented. A clearly established purpose enables leaders to guide, assess, and accomplish development. The principles for developing leaders describe goals for what leaders need to be developed to do: lead by example, develop subordinates, create a positive environment for learning, exercise mission command, adaptive performance, critical and creative thinking, and know subordinates and their families.

Do you have clear purpose for why, what, when and how you want to develop?

Is developing others part of your self-development plan? How might you add this?

Why is knowing subordinates and their families one of the described goals?

When you develop your goals, one straightforward way in which you might characterize them is between who you want and need to be, what you want and need to know, and what you want and need to do.

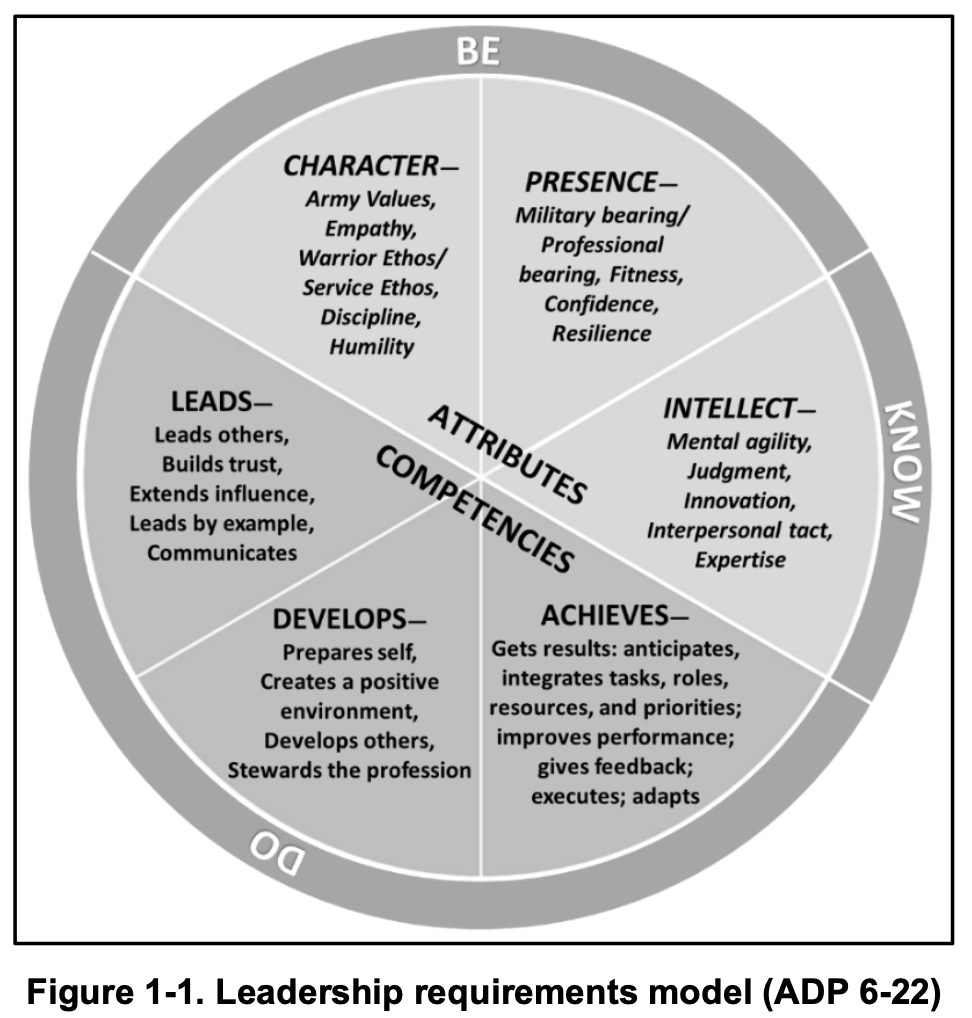

The US Army combines these into their leadership requirements model: who you need to be, what you need to know, what you need to do.

Apart from some very specific military language, this model can serve, with purpose, for any of us. But it can also easily be tailored. Give it a try:

How easy or challenging was it to fill in these blanks?

Do you find the ratio (space allocation) of Be - Know - Do to match your needs?

How would you modify this model?

Development in the institutional domain typically takes place in a classroom environment. Development in the operational domain is by its nature a group activity (based on interactions in real life). Even self-development, while independent in its source of inspiration, structure, and energy, is not solitary-development.

Leaders are for teams and are of teams; the US Army, in laying down its core principles for good leader development, stresses the criticality of teams and teamwork in the journey.

1-18. Three qualities characterize good teamwork: climate, identity, and cohesion. Climate refers to how members think and feel about their organization, based on shared perceptions and attitudes. It depends on the personalities within a unit, which change as people come and go. Team identity develops through a shared understanding of what the team exists to do and what the team values. Cohesion is the unity or togetherness across team members and forms from mutual trust, cooperation, and confidence. Teamwork increases when teams operate in a positive, engaging, and emotionally safe environment.

FM 6-22 goes further to define what an effective team looks like and does (there are entire manuals on teams, from which we’ll borrow with pride in the future).

Table 1-2

Effective Teams

Emphasize commonalities among members rather than characteristics that cause subgroups to form.

Hold a shared vision about operating as a team.

Share useful information with other team members.

Ensure team members join group activities (such as sports, meals, or other off-duty activities).

Act quickly to promote togetherness when schisms in the group appear or morale drops.

Show appreciation and concern for team members.

Act as a team instead of individuals; take pride in team accomplishments.

Developing leaders requires a strong support structure to help create accountability the training, education, and experiences of the journey.

What teams support your leader development?

Are you on teams that reflect the above characteristics?

What does your team need to improve?

Leader development, guided by your purpose and goals, supported by three domains, reinforced by teams, evolves over the course of a career and life.

1-25. In addition to the leadership requirements model, leaders must grow in their ability to understand, visualize, describe, direct, lead, and assess under differing conditions changing at each leadership level. As leaders progress, they experience greater challenges based on the situation’s scope, the consequences and risks involved, and the time horizon. As scope increases, the number of people and outside parties involved increases. The consequences of decisions increase, as do the risks that leaders must address. The length of time that leaders’ decisions apply tend to increase at higher levels as well as the time over which leaders can apply influence.

The farther your progression, the greater the responsibility and the more lasting the ramifications of your leadership. It is not a linear path upward; transitions, whether they are promotions or life changes (marriage, parenthood, etc) create step-change increases in expectations. It will usually result in temporary gaps.

1-26. Career transitions can be difficult, regardless of performance and potential at prior levels. When moving into new roles with different demands, individuals may not perform at a previous high level. Individuals must have a developmental mindset to improve what is within their capability and be motivated to do their best. Their leaders have a responsibility to develop the capability.

This is self-evident when we are in these moments; inflection points between leadership levels, titles, and formal (or informal) changes to responsibility are opportunities to invest in and further embrace leader development. The ‘reward’ for the increase is an immediate need to improve. Though we can see this for ourselves, is this a perspective we acknowledge (and a grace we extend) for others? Especially subordinates?

1-27. The required attributes and the expected competencies leaders perform do not change. However, some attributes and skills become more important in certain positions based on leader level and responsibilities (see transition descriptions). Proficiency levels regarding leader performance are specific to the individual leader, not their age, rank, cohort, or assigned position. Leaders of all ability levels should take advantage of opportunities to improve.

How do you plan for future leader development needs?

When are there opportunities to ‘rest’ during a leader development journey?

The US Army defines six leadership levels for the organization, corresponding to increases in responsibility, personnel impacted, and significance of issues and impact.

The first three levels, direct, organizational, and functional leadership, are most closely associated with the first half of a professional career. Tied to age, they are roles that are typically relevant in your 20’s through mid-30’s.

1-28. Leading at the direct level. Initial-entry Soldiers and DA Civilians transition from a focus on self to providing direct leadership to others to accomplish missions. Junior leaders learn how to plan daily tasks and activities, understand organizational constructs, and interact with subordinates, peers, and superiors.

Leading organizations. The second transition occurs with leaders at the organizational level. This level begins at company, battery, troop, staff, and similar organization levels for DA Civilians. Direct level leadership still occurs at this level, but the leaders become leaders of leaders and rarely perform individual tasks, unless they serve in undermanned organizations or an emergency. Coaching subordinate, direct-line leaders and setting a positive example as a leader are two characteristics that stand out at this level.

Leading functions. The third transition is from leading an organization (as a leader of direct-line leaders) to leading functions. This level involves directing functions beyond a single individual’s experience path. Key characteristics are operating with other leaders of leaders and adopting a longer-term perspective. Functional leaders typically include majors, mid-level warrant officers, and mid-level NCOs.

The fourth, fifth and sixth levels correspond to traditional mid-to-late career leadership in large enterprises.

Leading integration. A fourth transition occurs when leaders assume command and leadership responsibility for battalion and similar-sized generating force organizations. These leaders must become more adept at establishing and communicating a vision and deciding on goals and mission outcomes. They need to find time for reflection and analysis and value the importance of making trade-offs between future goals and current needs. Positive attitudes related to trust, accepting advice, and accepting feedback pays dividends at this level and into the future.

Leading large organizations. A fifth transition occurs at the brigade-equivalent and higher levels of operational and institutional organizations. They often operate outside their experience paths while leading others operating beyond theirs as well. Leaders will only be successful by valuing others’ expertise and success. Humility is a desired characteristic of organizational and strategic leaders who should recognize that others have specialized expertise indispensable to success. A modest view of one's own importance underscores an essential element to foster cooperation across organizations. Even the humblest person needs to guard against an imperceptible ego inflation when constantly exposed to high levels of attention and opportunities.

Leading the enterprise. A final step occurs in the transition to serving as an enterprise leader. Enterprise leaders must be long-term, visionary thinkers who spend considerable time interacting with agencies beyond the military. This leader must be willing to relinquish control of enterprise elements to strategic and junior-level leaders.

These are not completely rigid and they will clearly vary from industry to industry. For entrepreneurs and those in non-profit, the transitions might be faster and the stack flatter. But recognizing where the transitions are, what the evolution in expectations are, and how they should inform your leader development are critical.

What level are you at? Where to aspire to be?

Do these transitions correspond to career steps in your organization? Where do they differ?

What do these transitions imply for your leader development?

How much do you work on your own development?

Questions for Individual Reflection

How might your organization's routine activities, which may seem mundane, serve as untapped leadership development opportunities?

FM 6-22 emphasizes that "the most effective developmental experiences occur in the operational domain, during daily interactions with subordinates." In what ways might your current leadership approach be overlooking these daily interactions as development opportunities?

At what transition point in your career did you feel least prepared, and what lessons from that experience inform how you develop other leaders today?

If leadership quality is truly an organization's primary competitive advantage, how should that be reflected in its talent development strategy change?

In what ways might your organization's stability and established processes be inadvertently hindering the development of adaptive leadership?

Professional Discussion Prompts

The Army emphasizes "experiential learning that is consistent with the principle of train as you fight." How might your organization redesign leadership development programs to better simulate the actual challenges executives face?

How balanced is your organization's approach to developing leaders through formal education, operational experience, and self-development?

How effectively does your organization’s succession planning process prepare high-potential leaders for their next level of responsibility?

As one progresses through leader transitions, the stakeholder environment becomes more complex. How comprehensively do your development programs prepare leaders to navigate the stakeholder environments they'll face?

How should an organization balance consistency in addressing performance issues with the need for situational leadership?

Personal Discussion Prompts

The text describes "development as a continuous process encompassing almost everything they do regardless of context." How do your non-work activities and relationships contribute to your leader development?

"Counterproductive leadership" can emerge "especially during stress, high operating tempo, or other chaotic conditions." How do you recognize and manage your own counterproductive tendencies during personal crises?

How have your expectations of your children's development been influenced by your professional leadership experience?

How have your personal responsibilities evolved in parallel with your professional advancement, and where have you struggled to balance the two?

Exercises

Development Interaction Audit

Exercise:

Identify five routine business interactions that occur in your organization (staff meetings, performance reviews, project updates, etc.).

For each interaction, analyze: 1) Current developmental value, 2) Missed development opportunities, and 3) Specific changes to transform the interaction into a powerful leader development opportunity.

Create a pitch explaining how transforming an interaction could significantly enhance leadership development.

Debrief:

Which routine interactions have the greatest untapped potential for development?

What organizational barriers prevent these interactions from being optimized for leader development?

How might restructuring these interactions affect business performance metrics beyond leader development?

Leader Transition Gap Analysis

Exercise:

Map the specific leadership transitions in your organization (i.e., individual contributor to team lead, director to VP, etc.).

For each transition, identify: 1) Critical skills/knowledge needed, 2) Current leader development offerings, and 3) Capability gaps that remain unfilled.

Prioritize the three most critical gaps and propose development interventions.

Debrief:

Which transition points create the greatest risk to organizational performance?

How do these transition gaps affect talent retention and engagement?

What informal practices have emerged to compensate for formal development gaps? Are they helpful or hurtful, and what should be adjusted?

Feel free to borrow this with pride and use with your teams, professionally or personally. If you do, please let me know how it went and tips for improvement: matt @ borrowingwithpride.com