Command & Staff

Guided Discovery.

Are you a good staff member?

Suggested Reading

FM 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations

Pages 2-1 through 2-34 based on printed document (PDF pages 21-54)

Overview of staff organization and roles within a headquarters, including expectations and responsibilities by position

This week’s Study: CCIRs

All excerpts below are from FM 6-0

Guided Discovery

I did not join the US Army with a plan to make it a career. And I didn’t.

When I separated from active duty it was not because I had a robust plan for my civilian career, rather I had a strong belief that I would not enjoy the next few years of a military career.

As a young Captain, I had already had a company-level command (typically you do not get a second command) and the next role I had any real interest in - Foreign Area Officer - was only available to Majors (a promotion that was many years away). It was almost certain that the next three to four years would be spent doing staff roles. To me, this was none of the leadership opportunity I was seeking and all of the administrative nonsense I dreaded. Anything in the civilian world would be better.

A jaded perspective, to be sure. I was impatient.

But it was not a unique perspective. Most people do not actively seek out administrative work and for those inclined towards a career of increasing leadership responsibility, being on staff looks like an off ramp or detour.

Is it?

2-2. Staff activities focus on assisting the commander in accomplishing the mission. Staffs support commanders in understanding, visualizing, and describing an operational environment (OE); making and articulating timely decisions; and directing, leading, and assessing military operations. They make recommendations and prepare plans and orders for their commander.

Staff time is an opportunity to develop knowledge about how a larger organization is or is not successful in advance of becoming responsible for leading that larger organization.

Instead of an off ramp or detour, staff time is rotational development to give exposure to complexity before assigning responsibility for complexity.

2-4. Staffs support and advise their commander within their area of expertise. While commanders make key decisions, they are not the only decision makers. Trained and trusted staff members, given decision-making authority based on the commander’s intent, free commanders from routine decisions. This enables commanders to focus on key aspects of operations.

Good leaders empower their staff to act as an extension of the commander. The ability to build and strengthen a staff is a core leadership skill. And this skill is best developed by leaders spending time being on staff. Live the experience to learn the experience.

The ability to discern what information is relevant and critical to decision-making is fundamental to a leader’s success in navigating overwhelming complexity. Being on staff is the learning opportunity to be a relevance filter for a more senior leader and get practice making recommendations.

2-6. Staffs keep units outside their own headquarters well informed. … As soon as a staff receives information and determines its relevancy, that staff passes that information to the appropriate headquarters. The key is relevance, not volume. Large amounts of data may distract staffs from relevant information.

A leader of a large staff must have a complete understanding of what constitutes a good staff and what it means to be a good staff member. That understanding is gained, in part, by taking advantage of opportunities to be a good staff member.

Are you a good staff member?

Have you sought staff roles or actively avoided them? When are staff roles attractive?

What in charge, how do you feel when a staff's expertise exceeds your own in critical areas?

The worst case scenario for staff roles is administrative tasks and boredom.

The best case scenario? A lot of work.

2-8. Staff members have specific duties and responsibilities associated with their area of expertise. They must be ready to advise the commander and other senior leaders regarding issues pertaining to their areas of expertise without advance notice. However, regardless of their career field or duty billet, all staff sections share a common set of duties and responsibilities:

Managing information within their area of expertise.

Building and maintaining running estimates.

Conducting staff research and analyzing problems.

Performing intelligence preparation of the battlefield.

Developing information requirements.

Advising and informing the commander.

Providing recommendations.

Preparing plans, orders, and other staff writing.

Exercising staff supervision.

Performing risk management.

Assessing operations.

Conducting staff inspections and assistance visits.

Performing staff administrative procedures.

There is a lot of work and opportunity to learn for a leader on staff if the full set of duties and responsibilities are embraced.

Much of this week’s suggested reading in FM 6-0 is spent in defining staff roles, but analysis with a non-military lens provides tremendous lessons between the acronyms and technical nomenclature:

Characteristics of Effective Staff Members

Basic Staff Structure and Requirements

How to Build Your Personal Staff

How have you prepared for staff roles?

What do you expect from those on your staff?

Is there such a thing as too much staff coordination?

How should a leader distinguish between staff members who anticipate your needs versus those who create dependencies?

Characteristics of Effective Staff Members

To be a staff member is to be part of a team.

2-30. The commander’s staff must function as a single, cohesive unit—a team. Effective staff members know their respective responsibilities and duties. They are also familiar with the responsibilities and duties of other staff members.

One of the training techniques used with junior officers is to train them on all the activities performed the servicemembers in their command. If you are an artillery officer, you learn all the positions on the gun line, in the fire direction center, and in observation. Not because the officer will need to perform the activities themselves, but because the learning generates an appreciation for the integrated and dependent responsibilities of the entire team.

Staff members, with more seniority, do not need to be trained on every activity in the headquarters, but they are expected to be familiar with all parallel functions. In addition to having familiarity the complete responsibilities and duties of the staff, staff members are expected to exhibit the follow personal characteristics:

Are competent.

Bring clarity.

Exercise initiative.

Apply critical and creative thinking.

Are adaptive.

Are flexible.

Possess discipline and self-confidence.

Are team players.

An unsurprising list.

But consider it another way:

Competence as a staff member is table stakes. A good staff member should be working towards more external and advanced attributes, to provide a leader initiative and critical thinking. The ideal staff member is highly adaptable (not the same as flexible) and is able to evolve themselves as situations and requirements change. The behaviors a good staff member needs to move up and to the right are the remainder of the US Army’s suggested characteristics: discipline, creativity, and self-confidence.

Being on staff is not an occasion to fade into the background but rather an opportunity to demonstrate capability through proactive preparation and recommendation in support of the commander’s intent.

2-31. They understand that all staff work serves the commander, even if the commander rejects the resulting recommendation. Staff members do not give a partial effort, even if they think the commander will disagree with their recommendations. Alternative and possibly unpopular ideas or points of view assist commanders in making the best possible decisions.

No corporate staff role comes with a requirement of batting 1.000 in front of the boss, but many are treated like it is in the job description. There is no staff that does not hedge, pull punches, tread lightly, or rely on consensus and uniformity to minimize the risk of having a recommendation overruled by their leader.

Humans do not like being wrong. Which is the wrong way to think for a good staff member. Obviously the point is not to be wrong, but to not fear offering a contrary opinion.

We should give a full effort in support of our point of view until a decision is made, then we should give a full effort in support of the decision, whatever it might be.

Now let’s discuss the characteristic of adaptability a bit more, a critically important characteristic for staff members due to life’s most consistent challenge…

2-31. They avoid becoming overwhelmed or frustrated by changing requirements and priorities.

Adaptability is supported by discipline.

2-31. They anticipate requirements rather than waiting for instructions. They anticipate what the commander needs to accomplish the mission and prepare answers to potential questions before they are asked.

Adaptability is supported by self-confidence.

2-31. As critical thinkers, staff members discern truth in situations where direct observation is insufficient, impossible, or impractical. They determine whether adequate justification exists to accept conclusions as true, based on a given inference or argument. As creative thinkers, staff members look at different options to solve problems. They use innovative approaches by drawing from previous experience or developing new ideas. In both instances, staff members use creative thinking to apply imagination and depart from the old way of doing things when appropriate.

Adaptability is supported by creativity.

How does the US Army’s list of characteristics resonate with you? What is missing?

Have you experienced staff roles that require or engender creative thinking? What is required to encourage creativity in staff roles?

When should a leader ignore their staff's unanimous recommendation? How should a staff respond when this happens?

Basic Staff Structure and Requirements

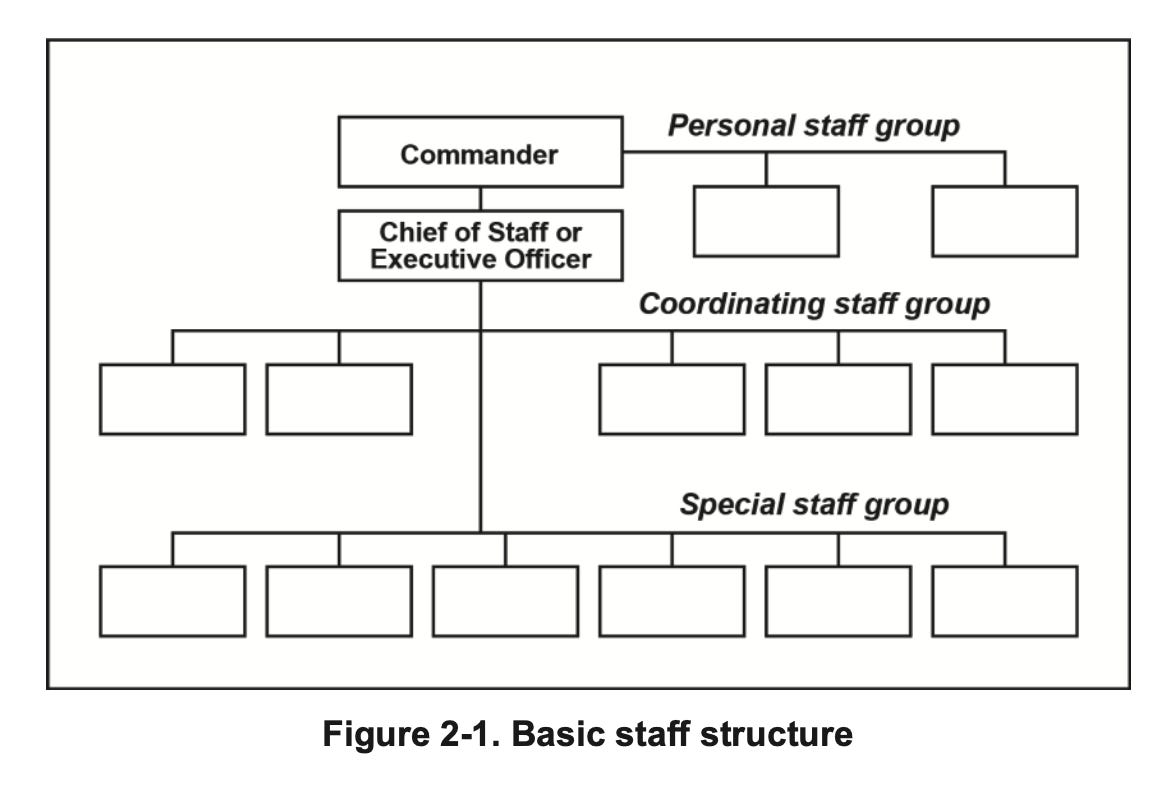

2-41. The basic staff structure includes a COS or executive officer (XO) and various staff sections. The position is titled COS at division and above, but XO at brigade and battalion. A staff section is a grouping of staff members by area of expertise. There are three basic types of staff officers: coordinating, special, and personal.

Is this how your organization looks? Of course not. But its not not how your organization looks.

There is logic in being formulaic and simply structured. People in the military switch roles frequently - why should they need to learn a new staff structure every time they move between units?

In the corporate world, there is a tremendous amount of consulting revenue generated annually helping organizations standardize their staff structures across various offices.

It is a problem of design and staff member behavior. At one end of the staff member behavioral spectrum? Avoiding work and shifting responsibility. At the other end? Empire building. Both leave an organization more complex and farther from a basic staff structure than is desirable.

On the US Army’s basic staff structure, apart from the Commander, there is only one other titled role: Chief of Staff (COS) or Executive Officer (XO).

2-43. The COS or XO is the commander’s principal staff officer. Commanders normally delegate executive management authority to the COS or XO, who typically also has successful command experience at lower echelons. As the key staff integrator, the COS or XO frees the commander from routine details of staff operations and the management of the headquarters. The COS or XO ensures the staff pulls together as a team and has good ésprit de corps, making the headquarters feel more like a cohesive unit rather than a large, impersonal organization.

In non-military organizations, a chief of staff is a coordination role, an empowered executive assistant responsible for organizing and metering the flow of people and information to and from a leader. They might have additional special project responsibilities. They probably get frequent after-hours calls.

A COS or XO in the US Army becomes the acting commander when the actual commander is not present. When the actual commander is present, the COS or XO functions as the right hand.

After that we have three types of staff members: coordinating, special and personal. Though we do not refer to staffs in this manner in our professional or personal lives, we all follow a nearly identical format (albeit generally with fewer roles than a brigade or division headquarters).

2-44. Coordinating staff officers are the commander’s principal staff assistants who advise, plan, and coordinate actions of special staff officers within their area of expertise.

Coordinating staff positions are what should be thought of as permanent staff roles. They have and will always exist. HR functions, finance functions, supply chain or operations functions; they are core to any organization and must always be staffed. The US Army leaves no mystery to a unit’s structure: every unit above a battalion uses the same labels and alphanumerics to indicate roles and responsibilities on coordinating staffs.

2-46. Organizations commanded by a general officer have G-staffs. Organizations commanded by field grade officers have S-staffs. The coordinating staff consists of the following positions:

ACOS, G-1—assistant chief of staff, personnel or S-1.

ACOS, G-2—assistant chief of staff, intelligence or S-2.

ACOS, G-3—assistant chief of staff, operations or S-3.

ACOS, G-4—assistant chief of staff, logistics or S-4.

ACOS, G-5—assistant chief of staff, plans.

ACOS, G-6—assistant chief of staff, signal or S-6.

ACOS, G-8—assistant chief of staff, financial management.

ACOS, G-9—assistant chief of staff, civil affairs operations or S-9.

Chief of fires or deputy fire support coordinator (DFSCOORD).

Chief of protection.

Support operations officer (SPO).

It’s formulaic and immensely helpful.

A well structured staff should not have any ambiguity in the responsibilities of coordinating staff. That does not mean there might not be gaps.

Which is where special staff comes in. FM 6-0 provides an exhaustive list of special staff roles, almost none of which are relevant beyond the military (though a Military Deception Officer might be a good person to hang with in a break room). But the roles exist when requirements create gaps between coordinating roles that can only be filled with expertise.

Whether the staff members are in coordinating positions or special positions, the US Army has two standing suggestions.

First: if the role exists it needs to be filled. An unstaffed role weakens the entire time and deprives a leader of information and guidance.

2-33. However, frequent personnel changes and augmentation to their headquarters adds challenges to building and maintaining a team. While all staff sections have clearly defined functional responsibilities, none can operate effectively in isolation. Therefore, coordination is extremely important. Commanders ensure staff sections are properly equipped and manned. This allows staffs to efficiently work within their headquarters and with their counterparts in other headquarters.

Second, regardless of the role, individual staff decisions still require frankness and confidence decision-making within the parameters of the role.

2-32. Although commanders are the principal decision makers, individual staff officers make decisions within their authority based on broad guidance and unit SOPs. Commanders insist on frank collaboration between themselves and their staff officers.

Should staff effectiveness be measured by agreement or by conflict?

Does the "chief of staff" model scale effectively in matrix organizations?

When do specialized staff roles create more silos than solutions?

What is the relationship between staff complexity and organizational agility?

How to Build Your Personal Staff

A military commander’s personal staff consists of roles that serve dual functions, with responsibility to support the commander on a personal basis (within their leadership capacity) as well as support the entire unit under the commander.

2-129. Personal staff officers work under the immediate control of, and have direct access to, the commander. By law or regulation, personal staff officers have a unique relationship with the commander. … Personal staff officers include—

Aide-de-camp.

Chaplain.

Inspector general.

Internal review officer.

Public affairs officer.

Safety officer.

Staff judge advocate.

Surgeon.

Unintentionally, the US Army’s prescribed personal staff roles align to informal expectations of professional staff positions and suggest a structure personal staffs we might create for ourselves.

Four of the roles might even be considered the extrasensory characteristics needed to support a leader.

The Chaplain is the Ethical Advisor (Nose)

2-131. The chaplain assists the commander in the responsibility to provide for the free exercise of religion, and to provide religious, moral, and ethical leadership to sustain a ready force of resilient and ethical Soldiers and leaders. … This officer provides religious, moral, and ethical advisement to the commander as they impact both individuals and the organization’s mission.

As a staff member, how do you help your leader sniff out and resolve moral and ethical issues before they become crises? When building your personal staff, who can you rely upon for this input?

The Inspector General is the Therapist (Ears)

2-134. The inspector general (IG) is responsible for advising the commander on the command’s overall welfare and state of discipline. The IG is a confidential advisor to the commander.

As a staff member, how do you listen to and diagnose the state of the organization, and how do you play that information back to your leader? When building your personal staff, who supports you by listening to you and listening for you?

The Internal Review Officer is the Professional Coach (Eyes)

2-136. The internal review officer is responsible for providing internal audit capability. … The internal review officer provides information and advice on evaluating risk, assessing management control measures, fostering stewardship, and improving the quality, economy, and efficiency of business practices.

As a staff member, do you tell it like you see it? When building your personal staff, who have you authorized to observe and provide you with brutal truth and coaching?

The Public Affairs Officer is Your Champion (Mouth)

2-138. The public affairs officer (PAO) is responsible for coordinating and synchronizing themes and messages and advising the commander on public affairs. The PAO provides the communication expertise required to advise commanders in aspects of information and communication regarding external audiences and public communication. The PAO is responsible for coordinating and synchronizing themes and messages through effective planning while ensuring unity of effort throughout an information environment.

As a staff member, do you appropriate advocate to external audiences and understand how to stay on theme? When building your personal staff, have you identified who can be trusted to advocate for you in the rooms in which decisions are made?

What personal "staff functions" do you delegate in your family life?

How do you prevent your staff from becoming an echo chamber while maintaining loyalty?

What personal rituals help you process information without staff influence?

A leader does not need to love staff roles, but they need to embrace them as part of their development process. It is unlikely we will be successful leading staffs if we were unable to demonstrate an ability to be a good staff member ourselves.

2-148. Staff officers must be subject matter experts in their own fields, integrate as a member of the staff, and be flexible and able to anticipate and solve complex problems sets. They must anticipate problems and generate and preserve options for the commander to make timely decisions. They must be leaders.

Are you a good staff member?

Questions for Individual Reflection

What's the optimal ratio of ‘devil's advocates’ to ‘yes-people’ on your team?

How should a leader balance staff integration with individual accountability?

When does staff loyalty become an organizational weakness?

How do you distinguish between staff expertise and staff empire-building? Is empire-building ever okay?

When in a leadership role, how do you tell the difference between being informed and being overwhelmed by your team?

Professional Discussion Prompts

What's the business case for maintaining staff functions that do not directly generate revenue? Are the expectations different for these roles?

Should functional expertise be prioritized over leadership capability in staff appointments?

How should an organization estimate the ROI of investing in staff development versus external consulting?

How do you prevent staff roles from becoming political positions rather than operational ones?

Should staff members rotate through line positions, or vice versa?

Personal Discussion Prompts

What role does trust versus verification play in your staff relationships?

When have you been most vulnerable to staff manipulation or agenda-setting?

What aspects of delegation feel most threatening to your sense of control?

How do you manage the people who manage your life?

How do you handle staff who know your weaknesses better than you do?

Exercises

Coordination vs. Speed

Exercise:

Map a recent organizational decision showing all points of coordination.

Calculate the actual time spent on coordination versus decision quality improvement.

Identify points where coordination did or might have led to organizational paralysis.

Debrief:

Where does coordination in your organization add theater rather than value?

How do you distinguish necessary coordination from bureaucratic habit?

What happens when coordination becomes an excuse for avoiding decisions?

Decision-Making Traps

Exercise:

Each participant identifies one decision they routinely make that could be delegated to subordinates.

Discuss what prevents delegation: control, trust, or organizational design.

Discuss the gap between theoretical delegation and actual practice.

Debrief:

What decisions do you keep for yourself that your staff could handle better?

When does your need for control undermine your team's effectiveness?

Where might have over-delegation created more problems than solutions?

Feel free to borrow this with pride and use with your teams, professionally or personally. If you do, please let me know how it went and tips for improvement: matt @ borrowingwithpride.com

![No Spoilers] Happy 51st birthday to the best Hand of the King/Queen Tyrion Lannister/Peter Dinklage : r/gameofthrones No Spoilers] Happy 51st birthday to the best Hand of the King/Queen Tyrion Lannister/Peter Dinklage : r/gameofthrones](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CyBo!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe132a703-482c-4697-9345-3eed2efe40e9_452x679.jpeg)